Why a site devoted to James Branch Cabell? For a brief spell in the 1920s, Cabell (1879-1958) was one of the most famous writers in America. Today, in the 21st century, many people – even educated and literate people – have never heard of him. And many of those who do know the name think of Cabell as a one-book writer – as he feared, he is remembered as “the author of Jurgen” and Jurgen is by the many recalled only dimly as a relic of the Roaring 20s, a smutty escapist fantasy.

Why a site devoted to James Branch Cabell? For a brief spell in the 1920s, Cabell (1879-1958) was one of the most famous writers in America. Today, in the 21st century, many people – even educated and literate people – have never heard of him. And many of those who do know the name think of Cabell as a one-book writer – as he feared, he is remembered as “the author of Jurgen” and Jurgen is by the many recalled only dimly as a relic of the Roaring 20s, a smutty escapist fantasy.

"I do not exactly like this," said Jurgen. "Upon my word, I do not like this at all. It does not seem fair. It is perfectly preposterous. Well"—and here he shrugged,—"well, and what could anybody expect to do about it?

It is indeed not fair for Cabell and his writings to be so neglected and misunderstood. Consequent to the uproar over Jurgen’s obscenity trial Cabell was type-cast as a leering sophist; and H. L. Mencken did him no favors by overselling his work to an American public which mostly didn’t know what to make of him. Cabell was no Scott Fitzgerald or Thorne Smith, as he has since proved not to be William Faulkner or J. R. R. Tolkien.

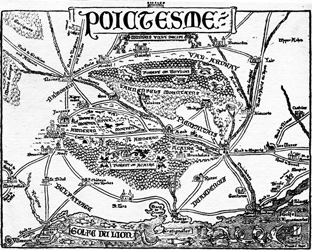

What kind of a writer was James Branch Cabell? This is part of the problem. Lin Carter once called Cabell “the only American author of genius to devote his career to fantasy” and now Michael Swanwick dismisses the bulk of Cabell’s work because it does not toe that line. But Cabell wore successively and successfully a number of literary masks. In the first decade of the last century he was lauded by Mark Twain and Theodore Roosevelt for the charm of his ironically romantic stories, and even the famous illustrator Howard Pyle, who felt conflicted about Cabell, admitted “Mr. Cabell’s stories… are very clever, and far above the average of magazine literature.” His literary manifestos, such as Beyond Life and Straws and Prayer-books, were attacked and defended in the daily papers. Edmund Wilson approached The Nightmare Has Triplets trilogy as a modernist work, comparing it with Joyce and considering it to be one of Cabell’s finest. An argument could be made for Cabell as a pioneer in ‘alternate history’ (see for instance the Satraps-Heritage-Scabbard trilogy of stories in Chivalry (1909) about the secret fate of England’s Richard II). In the 1950s he began to draw the attention of critics as a specifically ‘Southern’ writer, so that eventually Cabell’s biographer, the late Edgar E. MacDonald, summed him up as a “Southern allegorist.” (Perhaps we could call him a ‘Southern Belle Lettrist’?) It is true that some of Cabell’s best work did masquerade as high fantasy, though Jurgen fetched his life and being from works of royal siege, as The Golden Ass, and Candide, and Through the Looking Glass, rather than from more usual fantasy forefathers such as George MacDonald, William Morris or Rider Haggard. Cabell’s high fantastical writings are a great achievement, but they are only part of his achievement.

What kind of a writer was James Branch Cabell? This is part of the problem. Lin Carter once called Cabell “the only American author of genius to devote his career to fantasy” and now Michael Swanwick dismisses the bulk of Cabell’s work because it does not toe that line. But Cabell wore successively and successfully a number of literary masks. In the first decade of the last century he was lauded by Mark Twain and Theodore Roosevelt for the charm of his ironically romantic stories, and even the famous illustrator Howard Pyle, who felt conflicted about Cabell, admitted “Mr. Cabell’s stories… are very clever, and far above the average of magazine literature.” His literary manifestos, such as Beyond Life and Straws and Prayer-books, were attacked and defended in the daily papers. Edmund Wilson approached The Nightmare Has Triplets trilogy as a modernist work, comparing it with Joyce and considering it to be one of Cabell’s finest. An argument could be made for Cabell as a pioneer in ‘alternate history’ (see for instance the Satraps-Heritage-Scabbard trilogy of stories in Chivalry (1909) about the secret fate of England’s Richard II). In the 1950s he began to draw the attention of critics as a specifically ‘Southern’ writer, so that eventually Cabell’s biographer, the late Edgar E. MacDonald, summed him up as a “Southern allegorist.” (Perhaps we could call him a ‘Southern Belle Lettrist’?) It is true that some of Cabell’s best work did masquerade as high fantasy, though Jurgen fetched his life and being from works of royal siege, as The Golden Ass, and Candide, and Through the Looking Glass, rather than from more usual fantasy forefathers such as George MacDonald, William Morris or Rider Haggard. Cabell’s high fantastical writings are a great achievement, but they are only part of his achievement.

Why a site devoted to James Branch Cabell? O reason not the need! But let’s see… Cabell was a complex person who produced a complex body of work, and much could be done by contemporary critics to interrogate his attitudes concerning race, class, gender, sexual identity, politics, and aesthetics, not to mention his connections with more canonical writers and his status as a site of conflict in the society of the 1920s; as such he should reward close study. While all this is true enough, we need not justify our interest to the continual plodders. So why read and study his writing? because we like it! Cabell’s work is far from flawless, and tastes vary, but we find him a joy to read – witty, sly (in a good way), inventive, erudite (in a good way) and, even when irritating, always interesting. Finally, he had a long career, was a continual reviser, worked with numerous publishers and editors, producing a myriad books in a wide variety of bindings (fine and otherwise), often graced by some of the finest illustrators of his day – so that he is a fascinating subject for the book collector.

It is indeed not fair for Cabell to be so neglected and misunderstood. At The Silver Stallion, a collaborative website devoted to the study, collecting, and enjoyment of the writings of James Branch Cabell, we would like to do something about it. We are not the first and we are not alone – there are some excellent academic, fan, and personal pages devoted to Cabell scattered across the internet (see our Links page) - but they are scattered. In the 1960s and 1970s, during the First Cabell Revival there were actually two James Branch Cabell societies, each with its own journal (“Kalki” and “The Cabellian”). James N. Hall, the first “Kalki” editor produced the outstanding James Branch Cabell: A Complete Bibliography (1974) oriented towards collectors, to complement Frances Brewer’s more traditional James Branch Cabell: A Bibliography of his Writings, Biography and Criticism (1957). But Brewer and Hall, excellent as they are, are now decades out of date and their flaws have been noted. We thought it was time to use the visual and informational resources now available to produce an updated illustrated Master Bibliography based on, and extending, their work. And we hoped this bibliography, aside from being useful and pleasing to look at, could prove the keystone of a centralized meeting-place for those interested in Cabell, his works and his milieu, perhaps even jump-starting a Second Cabell Revival. Because for us, and for others —hunkered down in the libraries, thronging the fantasy cons, scattered across the blogs — Cabell lives.

It is indeed not fair for Cabell to be so neglected and misunderstood. At The Silver Stallion, a collaborative website devoted to the study, collecting, and enjoyment of the writings of James Branch Cabell, we would like to do something about it. We are not the first and we are not alone – there are some excellent academic, fan, and personal pages devoted to Cabell scattered across the internet (see our Links page) - but they are scattered. In the 1960s and 1970s, during the First Cabell Revival there were actually two James Branch Cabell societies, each with its own journal (“Kalki” and “The Cabellian”). James N. Hall, the first “Kalki” editor produced the outstanding James Branch Cabell: A Complete Bibliography (1974) oriented towards collectors, to complement Frances Brewer’s more traditional James Branch Cabell: A Bibliography of his Writings, Biography and Criticism (1957). But Brewer and Hall, excellent as they are, are now decades out of date and their flaws have been noted. We thought it was time to use the visual and informational resources now available to produce an updated illustrated Master Bibliography based on, and extending, their work. And we hoped this bibliography, aside from being useful and pleasing to look at, could prove the keystone of a centralized meeting-place for those interested in Cabell, his works and his milieu, perhaps even jump-starting a Second Cabell Revival. Because for us, and for others —hunkered down in the libraries, thronging the fantasy cons, scattered across the blogs — Cabell lives.

Why a site devoted to James Branch Cabell? It is not fair for Cabell to be so neglected and misunderstood, After all, when a man's writings cannot be understood nor a man's good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning on a Fairhaven street.

"Well, that seems only just" says Jurgen. "Yes, certainly you must deal fairly with me."