The Silver Stallion

An Interview With Paul Spencer

The Silver Stallion is pleased to present an interview with former Kalki editor Paul Spencer. Paul has been well-known in science fiction and fantasy circles since the late 1940s for his erudite introductions to anthologies and reprints, his occasional short stories, and his expertise on the writings of David H. Keller, A. Merritt, Edgar Rice Burroughs, L. Frank Baum and others, and of course, on James Branch Cabell. From 1967 he was secretary to the James Branch Cabell Society and their scholarly organ Kalki. When Kalki needed a new editor in 1975, Paul took up the baton and served as Kalki’s editor-in-chief from late 1975 until the final issue in 1993, continuing the fine work of his predecessors James N. Hall, James Blish and William L. Godshalk. Paul Spencer formerly worked in publishing in New York City, and now lives in retirement in New Hampshire. (Special thanks to Sue Mitchell for her help with this feature.)

was in need of a few bucks and it was a nice afternoon, so I took a stroll in the direction of Jurgen’s Pawnshop. I’d recently found a golden ring -- well, it appeared to be gold – while I was fishing. It had some elvish writing on it but I didn’t think my wife would let me propose to any elf maidens (LOL!) so I thought I might as well see what I could get for it. When I entered the pawnshop, M. Jurgen was chatting up one of the local dryads, so I scoped out the showcases to compare prices on any rings he might already have. While I was browsing, an older fellow wearing specs – rather distinguished-looking -- came in with a bundle under his arm. As the dryad slid into the backroom with a wink, he strode up to the counter and presented his parcel.

was in need of a few bucks and it was a nice afternoon, so I took a stroll in the direction of Jurgen’s Pawnshop. I’d recently found a golden ring -- well, it appeared to be gold – while I was fishing. It had some elvish writing on it but I didn’t think my wife would let me propose to any elf maidens (LOL!) so I thought I might as well see what I could get for it. When I entered the pawnshop, M. Jurgen was chatting up one of the local dryads, so I scoped out the showcases to compare prices on any rings he might already have. While I was browsing, an older fellow wearing specs – rather distinguished-looking -- came in with a bundle under his arm. As the dryad slid into the backroom with a wink, he strode up to the counter and presented his parcel.

“Bonjour M. Jurgen, “ quoth he, “I’m hoping you might be interested in the rare bit of literary ephemera I have here -- a copy of the program from the Colophon Club’s dinner in honor of James Branch Cabell. I'm afraid it isn't one of the signed programs --"

"Oh, we can fix that," says Jurgen...

"-- but it's still a pretty scarce collector's item."

“Hmmm,” replied Jurgen, “The market for Cabell isn’t what it used to be. Wait right here while I look it up on the internet. Do you want cash or credit?”

The fellow glanced quickly around at the bizarre assemblage of items on display, and replied, “Er, ah, cash I suppose.” “Be right back,” says Jurgen, and disappeared into the back room..

I stepped forward. “Say, aren’t you Paul Spencer?”

“Why, yes I am – do I know you?”

“No, but I saw you at the MLA Cabell seminar in 1973. You were on the staff of that Cabell journal, Kalki, and then a couple years later you became its editor. I was a subscriber then so I guess we were correspondents of a sort. As it happens I’ve kept my hand in as a Cabellian and now I’m involved in running a new James Branch Cabell website, somewhat in the spirit of Kalki. I wonder if I might interview you regarding your years as Kalki editor and as a Cabellian in general – we’ve already published an interview with William L Godshalk, your predecessor as Kalki editor.”

“Bill Godshalk! what a character! Sure, we can talk about the old days at Kalki, though I warn you it was a pretty long time ago, so I may be a bit sketchy on some of the details.”

“That’s all right. There’s a nice little coffee shop around the corner, The Place of Ecben – we can talk there.”

“What about M. Jurgen?”

“Oh, he won’t be back for a while,” I said, “Once you get on the internet, it’s hard to get off. Besides, I think that little dryad is probably helping him, uh, research your book…”

SS: So, Paul, how did you become a Cabellian? What led you to become a fan of James Branch Cabell’s writing?

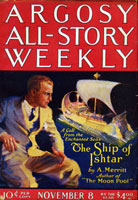

PS: It was a comment from the fantasy and science fiction author A. Merritt, whose work I liked. Merritt commented upon a third author. He said, "He's so good I almost like him as much as Cabell, and I like Cabell very much." And, of course, that made me think, "Who is this guy Cabell?" I looked up a book of Cabell's in the public library. It was The Cream of the Jest. I read that and just loved it and immediately started tracking down anything by or about Cabell that I could find.

PS: It was a comment from the fantasy and science fiction author A. Merritt, whose work I liked. Merritt commented upon a third author. He said, "He's so good I almost like him as much as Cabell, and I like Cabell very much." And, of course, that made me think, "Who is this guy Cabell?" I looked up a book of Cabell's in the public library. It was The Cream of the Jest. I read that and just loved it and immediately started tracking down anything by or about Cabell that I could find.

SS: What was it that appealed to you about it?

PS: It had a very inventive plot that went back and forth between the real world and a fantasy world, which was quite effective. The quality of the writing was superb. It was a great pleasure to see the way he put words together and put ideas across, usually with a real touch of wry humor.

SS: At that time, he was still alive, wasn't he?

PS: Yes, he was. In fact, I exchanged a couple of letters with him, which of course I have treasured ever since. They were just short notes. I remember that in the first one I got, he commented particularly on the fact that I had said I just loved his books although there were certain things in them that irritated me. He said, "What you said about my books really rings a bell with me because that's the way I feel about them, too."

SS: He was still publishing after you discovered him?

PS: Yes.

SS: So every time he came out with a new book, you would get it.

PS: I kept getting them as they came out. And then I collected all his older books and of course I’ve read everything that he has written. I have a few collector’s items as well. In fact I brought one today to show M. Jurgen.

PS: I kept getting them as they came out. And then I collected all his older books and of course I’ve read everything that he has written. I have a few collector’s items as well. In fact I brought one today to show M. Jurgen.

At some point, a bunch of Cabell’s admirers who styled themselves “The Colophon Club” put together a dinner for him. They were mostly distinguished literary people themselves, and I have a copy of the program for the evening. That's quite a unique Cabell item. And speaking of literary dinners, that reminds me of an amusing incident that occurred at another one Cabell attended – at Ellen Glasgow’s house I believe. Gertrude Stein – “Pigeons on the grass. Alas!” you know – and her companion Alice B. Toklas were there, and of course Stein’s writing was in a different universe than Cabell’s. At dinner Cabell was seated next to Miss Toklas and he asked her, “Is Gertrude Stein serious?” Toklas replied, “Desperately!” “Ah,” says Cabell, ”that puts a different light on it.” “For you,” says Toklas, “not for me.” Like a Gertrude Stein poem, we can interpret this in various ways…

SS: I wish I had been there. How did you come to be involved with Kalki?

PS: It was through James Blish…

SS: How did you know James Blish?

PS: James Blish was a science fiction writer of some note, so his name and some of his stories were familiar to me. Actually, the link is with Richard Strauss. Blish wrote an article about Strauss's opera Elektra. It appeared in I forget which fan magazine, probably one with a link to science fiction in some way. It was an excellent article about Elektra, and a great acknowledgement and appreciation of Richard Strauss, who is a favorite of mine. Well, Blish lived in one part of Manhattan and I lived in another part, so when I read his comments, I got in touch with him. Then, as I remember, he invited me to his apartment for dinner with him and his wife, and we became very friendly. We kept discovering more things that we shared an interest in -- and one of them was James Branch Cabell…

SS: Who else worked on Kalki when you were first involved in it? How did you meet them?

PS: Well, there was James Hall who started Kalki as a fanzine. I believe I saw a letter of his or an ad in a science fiction fan magazine. I was very excited to hear that I was not the only person in the world who liked Cabell and got in touch with him, and it went on from there. A number of the earliest contributors and subscribers were from the science fiction world, writers and editors like Gerry Page and Robert L. W. Lowndes. I got to know Lowndes. I would see his name in the letter columns of science fiction magazines, and when I moved to New York, I discovered he lived only a few blocks from me. So I got in touch with him and we got together, and it turned out we had some other interests in common—musical, as I recall. We were kind of pals, not real bosom buddies, but on quite friendly terms. And then there was Bill Godshalk, who was a college professor, at the University of Cincinnati I think. He eventually became Jim Blish’s co-editor, and over time more and more academics became involved in Kalki.

SS: There was another Cabell journal, wasn’t there, staffed almost entirely by college professors?

SS: There was another Cabell journal, wasn’t there, staffed almost entirely by college professors?

PS: Yes, The Cabellian. It was pretty good but it didn’t last very long. I remember Kalki and The Cabellian had a meeting together about joining each other, and Blish, our editor, was sort of the middle man. There was discussion about combining them, but it didn't work out. Their editor considered us to be rivals and it was a question of which journal would be the dominant one. As it turned out, we were the survivor.

SS: So, let’s see… according to the Kalki history on our website, James Blish moved to England in 1969 and Bill Godshalk became his co-editor, Then in 1971 Godshalk became sole editor with Blish as “editorial advisor,” and around 1973 Kalki cut back from four times to twice a year. Then in 1975, major changes: Blish died in England, and academic responsibilities caused Godshalk to reduce his commitment (after which Kalki became an annual), so you stepped up and assumed the Kalki editorship. Prior to that you had been Secretary of the James Branch Cabell Society.

PS: Yes, I had to fill the subscription orders. I had boxes full of back issues and it was my job to send them to the subscribers. In fact, I think I still have a box of back issues somewhere.

SS: Being editor must have been a lot of work for you.

PS: Well, I was able to use material that my predecessor had gathered. I did some editorial writing, like a column at the beginning of each issue, and writing the blurbs for the individual stories or whatever. I had a lot of help from my assistant editors, at first from Godshalk and William D. Jenkins, and later from Dorys Crow Grover and Harlan Umansky. We did about a dozen more issues between 1976 and 1993 but sometimes it feels as if I edited only one or two issues! I didn’t feel like the editor-in-chief, really, but I did work on it.

SS: There was some quality stuff in those later issues.

PS: Yes, one noteworthy thing we did was to reprint some of Cabell’s early stories. We reprinted his very first published story “As Played Before His Highness,” from 1902 I think, and compared it with later revisions. [See our reprint of this reprint, along with Paul Spencer’s insightful commentary.] We also reprinted a sort of predecessor to his most famous work, Jurgen, a story called “Some Ladies and Jurgen”. It was published in The Smart Set by H. L. Mencken, a pal of Cabell's. As Cabell was writing it he realized he was throwing away on a story ideas that would serve for a full-length novel, so after he sent the story off to Mencken he went ahead and wrote Jurgen the novel.

SS: One of my favorite pieces from the later issues is your article discussing the influence of Maurice Hewlett’s Brazenhead the Great on Jurgen.

SS: One of my favorite pieces from the later issues is your article discussing the influence of Maurice Hewlett’s Brazenhead the Great on Jurgen.

PS: Yes, Cabell said he had worshipped Hewlett's books when he was young, though he found many of his later ones less than satisfactory. Hewlett and Cabell even corresponded a bit, but then they had a terrible falling out after Hewlett wrote an insulting review of Figures of Earth, so that Cabell inserted an excoriating rebuttal at the end of The Lineage of Lichfield in which he portrayed Hewlett as a has-been. Well, I looked up Hewlett, and I found I liked him, too. I don't think he's anywhere near the level of Cabell, but he's a very enjoyable writer. He wrote a number of historical novels that, in a way, are very similar to the sort of thing Cabell wrote. But his style, at core, is not like Cabell’s though Cabell did borrow quite a number of superficial features from him. In one of the early Kalkis I wrote a survey of Hewlett’s work, pointing out some of these quirks-in-common. [See our reprint of both of Paul’s Spencer’s Kalki articles on Hewlett and Cabell: "After the Style of Maurice Hewlett" and "The Hewlett Influence: An Afterthought"].

SS: As the 80s wore on Kalki began appearing less frequently, sometimes only every couple years or so.

PS: After a certain point it died pretty fast because people were losing interest in it—not submitting material for it, not renewing their subscriptions and so on. Dorys Crow Grover and Harlan Umansky were a lot of help in the final years. A lot of Kalki business was conducted long distance but I actually met Dorys at an MLA meeting in New York. There was this peculiar, ill-fated move to have some kind of connection between the Cabell fans and the Faulkner fans. Of course, I was a fan of both Cabell and Faulkner, and we figured there must be others, but nothing much came of that idea. Dorys was a very nice person. She’s still with us -- she sent me a Christmas card last year! I remember Harlan Umansky pretty well. I think he's gone. I visited Umansky at his home, which was in New Jersey near the Hudson River. He showed me his Cabell collection. He had an interesting habit. I may have started this kind of thing but didn't do much of it, whereas he had been rather faithful. He had two copies of all of Cabell's books, one to keep nice and one to write annotations in, in pencil. He would write, in between the lines and in the margins and so on, his reflections on this and that page. That would be interesting to see now.

SS: It certainly would. I don’t know what became of Umansky’s books but you may be interested to know that in our collection we have his own copies of the complete runs of both Kalki and The Cabellian. It must have been a sad day when Kalki ceased publication.

PS: It was. I remember killing it. Or rather when I went to kill it, it was already dead. I drafted a valedictory editorial explaining to the subscribers that there would be no more issues after this one, for the reasons I’ve mentioned: lack of contributions and subscriptions. But in the end that intended final issue never appeared and so the one we put out in 1993 was the last.

SS: As a veteran Cabellian, do you have any reflections on Cabell’s work you’d like to share with us?

PS: I wrote an article called “Cabell: Fantasist of Reality” which was published in Darrell Schweitzer’s critical anthology Exploring Fantasy Worlds. As I mentioned earlier, the first book I read by Cabell was The Cream of the Jest, which came out in 1917. Cabell later said that he felt that everything he had written before that was written by somebody else. Now that I’ve read all his books, I understand that, because the earlier books are very different from those he wrote after 1917. Cream of the Jest is a very inventive and unusual book in which the fantastic and the everyday more or less intermingled. In many cases, the earlier stories were written in sort of a commercial way, aimed at big circulation magazines. He was trying to, as I say, satisfy editorial requirements. With The Cream of the Jest, it seems he wrote what he wanted to write-- after that he was pretty much on his own. What he wrote usually was sort of metaphorical and symbolic and so on, so he was really writing about reality, even when he was writing these exotic things. So you have that mixture in Cabell. As far as he was concerned, he was really writing about what life is like, what people are like. Then he became more fanciful later on, but it still was his way of interpreting life and humanity.

SS: Paul, this has been a fascinating conversation and I thank you in all sincerity for the granting of it. But we had better head back to the pawnshop to see if M. Jurgen has reached a decision. Did you finish your coffee? You want the last biscotti? You know, if he declines to buy your Colophon Club program might you be interested in trading it straight up for this golden ring I found? I’m not sure who it previously belonged to but I’m sure it can’t do any harm…